Families and Teachers Working Together for School Improvement Cherry a Mcgee Banks Review

This playbook on family unit-school collaboration makes the case for why family engagement is essential for instruction systems transformation and why families and schools must have a shared agreement of what a proficient quality education looks like. Past providing evidence-based strategies from around the world and other easily-on tools that school leaders and partners can prefer and use in their local contexts, it aims to help leapfrog education inequality so that all young people can take a 21st-century education.

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic has put the topic of families and schools working together to educate children at the center of almost every country'southward education debate. Teachers around the world report developing artistic means of engaging with parents to help their students learn at home, including strategies they would like to go on even later on pandemic is over (Teach for All, 2020; Teach for Pakistan, 2020). In turn, parents—whom nosotros define as any family members or guardians who are the primary caregivers (see Box 1 for of import terms divers)—have responded to these new remote-learning experiences and new forms of communication. Their increased expectations of deeper engagement with schools are reflected in representative surveys of parents across Republic of colombia, Mexico, Peru, and the United States—all pointing to this rising demand from families for new approaches to working with schools (Learning Heroes, 2020; Molina et al., 2020).

Many leaders of schools and school systems across the world had an "aha" moment when, after pivoting to new outreach and communication mechanisms, they saw major jumps in the level of appointment of families, especially amongst those who had been previously deemed hard to reach. From Argentina to India to the Usa, leaders realized that hard-to-reach families were not opposed to engaging with schools; it was just that the schools' approaches to appointment were getting in the fashion. For example, when the government of Himachal Pradesh, a land of almost vii 1000000 people in India, pivoted from request parents to come to schools for meetings to finding multiple ways for schools to come to parents—through text messages, WhatsApp groups, and Facebook posts—engagement levels jumped from 20 percentage to 80 per centum in two months (Brookings Institution, 2021).

I felt like I knew more during the schoolhouse closures what my child had been learning than the entire three and a half other years she's been in school.

Parent, U.s.

The four goals

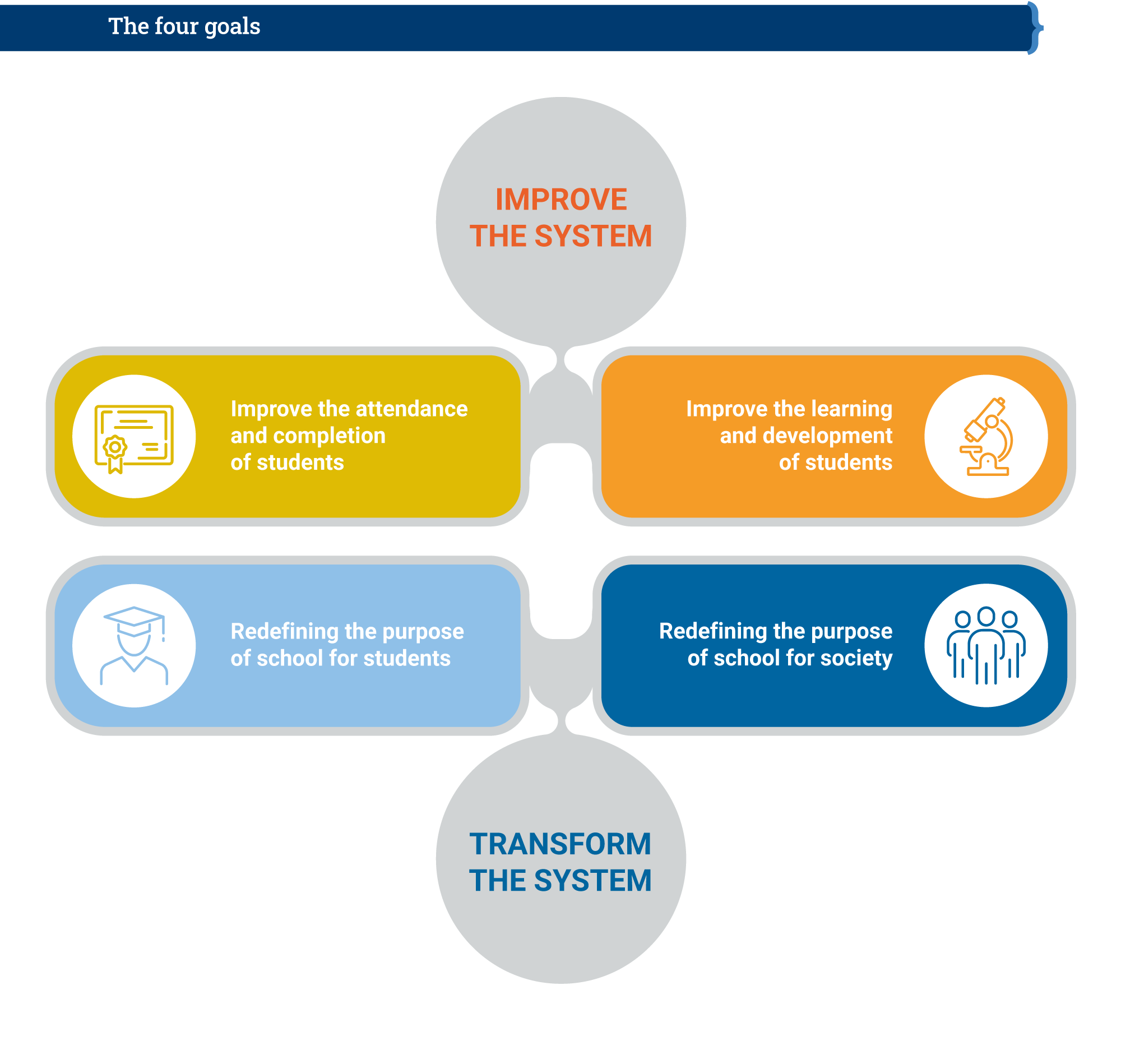

This new focus on ways to connect families with schools presents an opportunity to markedly shift broader approaches, and the overall vision, for long-term collaboration. This playbook shows that family-school engagement—namely the collaboration betwixt the multiple actors, from parents and community members to teachers and schoolhouse leaders—has an important role to play in improving and transforming education systems to accomplish 4 main goals (Effigy one):

Effigy 1

Box one Playbook terms defined

- Parent and family unit: In this playbook, "parent" is shorthand for any family unit member, caregiver, or guardian who cares for children and youth. We rely nearly heavily on the term "family unit" to capture the varied contexts in which children live and are cared for, including extended family members—from grandparents to aunts, uncles, or cousins—who play leading roles in caregiving. The playbook uses the terms "parent" and "family" interchangeably.

- Teacher: The playbook uses "teacher" instead of "educator" to distinguish between the educational activity professional (whose vocation is to instruct and guide children in school) and parents (who are their child's first educators, helping them develop and learn from birth on).

- Involvement versus engagement: We detect Ferlazzo'southward distinction between family unit "involvement" and "engagement" helpful and use the terms accordingly. "A school striving for family interest often leads with its mouth—identifying projects, needs, and goals and then telling parents how they tin contribute." In contrast, "a school striving for parent date leads with its ears—listening to what parents call up, dream, and worry about. The goal of family engagement is non to serve clients but to proceeds partners" (Ferlazzo, 2011, p. 12).

- Family-school engagement: This playbook uses the term "family-school date" instead of the more common "family unit engagement" non merely to express the dual nature of the engagement but also to highlight the fact that either side can, and does, initiate the appointment process.

- Alignment and the alignment gap: When families and schools share the same vision of the purpose of schoolhouse, they are aligned in their behavior and values, and this coherence is a powerful driver of education system transformation. An "alignment gap" exists when families and schools either do not share or perceive that they do not share the same views on the purpose of school and therefore what makes for a quality education for their children and communities.

- Schools and education systems: "Schoolhouse" denotes children'south structured process of teaching and learning regardless of location (whether a school building, outdoors, a library, a museum, or home). "Didactics systems" incorporate schools merely also frequently include a range of actors in the community (such as parks, employers, or nonprofit programs) that can piece of work with schools to provide an ecosystem of learning opportunities. Teaching systems tin have different levels of jurisdiction (district, state, or national) that denote their limits of authority. Although governments in every land deport the responsibility for ensuring that all children, particularly from marginalized communities, tin access a quality instruction, this playbook too refers to nongovernmental schoolhouse networks (for example, a individual school chain or a nonprofit network) every bit jurisdictions.

- System improvement: Sure efforts maximize how a system delivers instruction against the existing vision and set of outcomes. They aim to accomplish the showtime 2 goals defined in this playbook: (a) better student attendance and completion, and (b) improve educatee learning and development.

- System transformation: Other efforts broaden engagement to redefine the purpose of an education organisation, hence shifting the beliefs and mindsets that guide information technology along with the operations that deliver on that vision. They aim to achieve the second two goals defined in this playbook: (a) redefine the purpose of schoolhouse for students, and (b) redefine the purpose of school for society.

Improving education systems

Robust evidence shows that family unit-school appointment tin can significantly improve how systems serve their students, especially those who have been poorly served. Studies that primarily assess schoolhouse improvement have looked at students' educational outcomes as measured past omnipresence; completion; and accomplishment on literacy, numeracy, and other regularly assessed competencies. We classify these efforts as organization "improvement" because they improve how the system delivers education confronting an established gear up of outcomes rather than shifting the overall vision of the arrangement'south purpose. Several such studies find that family-school engagement, when implemented effectively, not simply boosts student outcomes but also can exist a highly cost-effective investment.

Our students come from very challenging backgrounds, so we cannot focus merely on academics. I feel it is necessary for teachers to spend some time bonding with students. It is very important for me to bond with their families as the difficulties faced past the families are also related to my child's groundwork. As a teacher, I feel having this consummate triangle connected to each other is very important.

Instructor, Bharat

Schools with strong family unit engagement are 10 times more than likely to improve student learning outcomes. In one longitudinal study across 200 public uncomplicated schools in Chicago (Bryk, 2010), researchers identified v key supports that together determined whether schools could substantially improve students' reading and math scores: school leadership, family and community engagement, pedagogy personnel chapters, school learning climate, and instructional guidance. Crucially, schools improved well-nigh when all five supports were nowadays. A sustained weakness in even one of these elements led schools to stagnate, showing little comeback.

The important part family unit-school engagement plays in improving students' achievement is also broadly supported by other research, including a meta-assay of 52 studies that constitute that engaging parents in their children'southward schooling leads to improved grades for students in their classes and on standardized tests (Jeynes, 2007).

Communicating with families tin be one of the almost highly toll-effective approaches. Robust family engagement, equally a core pillar of improving schools, certainly requires investment to shift mindsets and behaviors, merely i particular component of this endeavor—straight communication with families—is a highly cost-effective manner of improving student omnipresence and learning outcomes. A global study comparing evaluations of different types of education interventions (such every bit teacher training, materials provision, scholarships) across 46 low- and middle-income countries found sharing data about education to be at the top of the listing in terms of cost-effectiveness (Angrist et al., 2020). The study showed that a particular arroyo to communicating data is what improves student outcomes at scale, namely context-specific information virtually the benefits, costs, and quality of local schooling from a messenger that families and students trust. For example, information that assistance families and their children to amend appraise the specific benefits of staying and doing well in school (similar higher earnings and amend health) besides as to meliorate identify resources that could help students participate in higher teaching and sympathise the quality of schooling options available to them. In fact, targeted information campaigns almost the benefits of pedagogy for students tin can deliver the equivalent of three additional years of high-quality education for a low per student cost.

The Global Education Show Advisory Console identified communicating with families in this manner, including through videos or parents' meetings at schoolhouse, as a "nifty buy" for education systems. For a minor investment, information technology can significantly improve educatee outcomes on of import dimensions such every bit years of schooling and acquisition of literacy and numeracy skills across a large number of communities (Global Teaching Bear witness Advisory Console, 2020).

Transforming education systems

The increased attention to family-schoolhouse date also provides an opportunity for a broader debate and dialogue on the overall purpose of school. Families non only have increased expectations for ongoing engagement just also, in many contexts, have had forepart-row seats within the schooling procedure during the COVID-xix pandemic and take opinions on what a quality education should expect like for their children.

These discussions on the purpose of school would, of grade, include an examination of strategies to ensure that students are attention school and learning well there. Only they would likewise let parents and families and teachers and schools to take a pace back and ask each other, "What are schools for? What part should they play in guild? And what types of competencies and skills should schools help our children develop?"

No institution or one actor can reinvent the education system past themselves. So you need to spend the time to develop an answer to the question: What is it that nosotros desire for our children in this community? Only one time we concur on where we're trying to become, tin we and so work in coordination and know what our corresponding roles are. Developing this shared vision is what good leaders do.

District superintendent, Us

Nosotros refer to this broader engagement on the guiding vision of education as system "transformation" work because it does non accept the current instruction organization outcomes every bit a given. Although the family unit date literature offers only a limited focus on engaging families with this goal in listen, the organization transformation field offers substantial insight on the important function family-school engagement plays in this process—and what it takes to attain this appointment.

Redefining the purpose of teaching—one of the well-nigh powerful levers for sustainably transforming systems—requires participation past the whole community. Systems of whatever kind—education, health, or justice—are fabricated upwards of many elements, from the physical and visible (like people and resources) to the abstract and invisible (like group priorities and culture). Scholars of system dynamics point to changing "deep structures," which include the invisible elements of a system like values and beliefs, as one of the nigh effective means to transform what systems do (Gersick, 1991; Heracleous & Barrett, 2001). They fence that frequently, when leaders seek to modify the concrete or visible elements of a organization without changing the deep structures of behavior and values that guide that organization, the results corporeality to tinkering around the edges. Conversely, a shift in the beliefs and values that guide a system drives changes beyond the visible and invisible elements alike (Meadows, 2008; Munro et al., 2002).

In this way, adjustment around a shared vision of the purpose of school is a powerful fashion for schools and families to shape the deep structures guiding how schools operate. For example, in communities where families or teachers or students have dissimilar beliefs about what schoolhouse is for and hence what they should practice, schools are probable to struggle, beingness pulled in multiple directions or experiencing considerable headwinds to any changes that are fabricated. In contrast, communities with a well-aligned vision of the purpose of schoolhouse tin can motility forward constructively, with families, teachers, students, and others all playing their respective roles in helping to advance this vision. This blazon of family-schoolhouse engagement has the added benefit of helping sustain a vision of quality schooling beyond multiple political cycles. An Achilles' heel of didactics arrangement change is the curt tenure of leaders. In Latin America, for instance, most pedagogy ministers are only in office for an average of ii to three years, which frequently means a revolving door of priorities guiding the arrangement (Fiszbein & Saccucci, 2016).

Deep dialogue with families and schools is needed to unlock systemwide transformational processes. I study examined the greatest barriers to and enablers of systemwide change, tracking reform journeys beyond three countries: Canada, Finland, and Portugal (Barton, 2021). In all three cases, the chief bulwark was a misalignment between members of the customs—from pedagogy leaders to teachers to families—on their beliefs and values nigh school. They lacked a shared sense of "this is what school is nearly." In all three countries, a procedure of deep and respectful dialogue, whereby families and schools along with others had equal places at the table, was crucial for unlocking the organization transformation process. The study concludes that collectively defining and adjustment the purpose of didactics, and the values that bulldoze it, are among the essential enablers of systemwide transformation. This study reaffirms prior findings from U.Southward.-based enquiry: education reforms are only successful when, amongst other things, they are consistent with stakeholders' values, in other words when they are aligned to students, parents, and teachers' beliefs about instruction (Cohen and Mehta, 2017).

A irresolute earth

The COVID-19 pandemic has non been the start and volition not be the concluding external force driving a need to modify education systems. Strategies for families and communities to work together across all four goals of organization improvement or transformation are needed now, peculiarly to address the growing inequality that has emerged from the pandemic. Simply they volition also exist needed in the future to navigate the skills needed for a rapidly irresolute globe.

There is a growing consensus among educational activity experts and learning scientists that education systems must focus more heavily on ensuring that students develop a wide range of competencies—from robust academic knowledge, to "learning how to learn," to collaborative problem solving. Many as well hold that to develop this breadth of skills and deliver a holistic education, educational activity and learning experiences must shift to include more than experiential, playful, real-world application of academic learning (Winthrop et al., 2018). The forces that are already pushing pedagogy systems in this management are set to accelerate over the coming decades. They include the advent of new technologies, the disruption of the earth of work through automation of routine manual and cognitive skills, and the seriousness of complex social and ecology crises.

Although we subscribe to the argument that the fast pace of change requires education systems to improve and transform toward a more than holistic vision of education and accept written extensively on this earlier, we recognize that when it comes to family-schoolhouse engagement, prescribing a vision undercuts the very ability of the engagement process. For case, the deep dialogue needed to redefine the purpose of schools tin can only occur if parents and families and teachers and schools have an equal voice, whereby each brings their corresponding expertise to the table, and there is a level of trust that allows for the cocreation of a shared vision. We also realize that every context is different and together families, education professionals, students, and other stakeholders should be the ones to decide what a quality education looks like for them given their culture, history, aspirations, and community realities.

This is why this playbook focuses on offer means of understanding the full landscape of family unit-school date strategies then that communities may acquire from each other only ultimately with the goal of adapting and making strategies relevant in their own contexts. It is also why, to complement this mural of strategies, we accept provided an in-depth wait at ane of the system transformation goals: "redefine the purpose of schoolhouse for students." Current family-schoolhouse date work has focused much less energy and attention on transforming educational activity systems than on improving them, and deepening the field'due south agreement of how to arroyo this goal is 1 way of addressing this gap.

Playbook contributions

This playbook includes half dozen main components:

- Overview: We describe the 4 goals for family unit-school engagement (two goals for improving how systems serve students and two goals for transforming how systems are envisioned). The section provides context for family unit-school engagement in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and explains who should employ the playbook.

- Evolution: This section discusses the evolving nature of family-schoolhouse date. Historically, schools were never designed to engage families in the didactics of their children and we discuss the three main barriers facing family-school appointment today. We highlight the evolving story of good practice in family-school engagement from episodic involvement to continuous engagement.

- Strategy landscape: This section provides an overview of the good do strategies that stakeholders tin use to ameliorate family-school engagement. Information technology is a typology, or "map," for understanding the breadth of family unit-school engagement approaches for achieving each of the four goals and highlights findings from our review of over 500 strategies.

- Strategy Finder: This interactive database features more than sixty strategies from effectually the world that bring the strategy landscape to life.

- Aligning beliefs: This section provides an in-depth look at the third goal of family unit-school appointment: redefine the purpose of school for students. Information technology provides a framework for understanding how family unit-schoolhouse engagement tin can support system transformation and our insights from surveying close to 25,000 parents and more than half-dozen,000 teachers almost their teaching behavior. We conducted these surveys together with our Family Engagement in Didactics Network (FEEN) across 10 countries and one global private school chain.

- Conversation Starter tools: This section continues the in-depth look at redefining the purpose of school for students by sharing our "Conversation Starter" tools. These tools will help anyone begin exploring how to assistance families and schools accomplish a shared understanding of what a practiced-quality education looks like.

Whom is this playbook for?

This playbook is for anyone interested in helping families and schools piece of work better together to ameliorate or transform how education is delivered or what goals it achieves. Given the ability held by education system leaders and school heads, this playbook is specially focused on supporting them in agreement the why, what, and how of working jointly with families to improve or transform schools (as further described in Box 2, "Who should use this playbook?").

How was the playbook developed?

The playbook incorporates input from dozens of organizations and thousands of individuals around the earth as well as extensive strategy assay and research, as follows:

Box two Who should use this playbook?

We promise this playbook is particularly useful for school system leaders, instructor organizations, civil society partners, and funders. We also hope the many parent organizations around the globe, whose work we lift up and highlight, will notice this playbook helpful to their ongoing work. The list below is certainly non exhaustive, and if you notice yourself exterior of one of these groups, we encourage you to read on.

Education determination makers

- Jurisdiction leaders and administrators. At the broader systems level, the playbook tin can exist especially relevant for jurisdiction leaders and administrators at the district, state, and national levels, including jurisdiction-level governing boards, private sector school networks, and instruction leaders with oversight of key functions such as strategic planning, teacher grooming, and community engagement.

- School leaders and leadership teams. At the school level, the playbook is designed for school leaders, principals, and their executive leadership teams, including staff with responsibilities over community engagement and student success, too as any related school-level governing boards.

- Leadership training programs. In addition, the playbook can as well exist useful for trainers of schoolhouse leaders, such every bit universities. We hope the playbook can inspire content for curricula around family appointment and systems transformation.

Instructor leaders

- Instructor networks. Instructor unions, networks, and organizations will also find this playbook useful, especially in their piece of work on strategy, policy, and advocacy. Although the playbook is not designed for private teachers, much of its content addresses topics that teachers regularly talk over and that figure in their concerns.

- Teacher training programs. In addition, the playbook can besides exist useful for trainers of teachers, such every bit universities. We hope it can inspire content for curricula around family unit appointment and systems transformation.

Schoolhouse partners

- School partners. In addition to systems-level administrators and school-level leaders, the playbook is useful for the many partners of schools. This includes NGOs, including those that support delivery of education to children; individual sector organizations, such as for-profit education companies; and funders, including bilateral and multilateral agencies and philanthropic foundations.

- Parent organizations. We also designed the playbook for parent organizations—groups of parents that have organized themselves to provide input into school and customs-level bug, such as curricula, schoolhouse infrastructure, and public safety. These groups are well placed to advocate for strong family-school relationships, and nosotros promise the playbook will inspire learning from the other parent organizations featured in the Strategy Finder.

References

Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., von Wehrden, H., Abernethy, P., Ives, C. D., Jager, N. W., & Lang, D. J. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio, 46(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

Angrist, T., Evans, D. Thousand., Filmer, D., Glennerster, R., Rogers, F. H., and Sabarwal, S. (2020, October). How to meliorate education outcomes almost efficiently? A comparison of 150 interventions using the new learning-adapted years of schooling metric. Policy Inquiry Working Paper 9450, World Banking concern.

Baker, D. P. (2014). The schooled gild: The educational transformation of global culture. Stanford University Press.

Bryk, A. S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Phi Delta Kappan, 91(7), 23–xxx.

Bryk, A., Gomez, 1000., & Gunrow, A. (2011). Getting ideas into action: Edifice networked improvement communities in educational activity. In Chiliad. Hallinan (Ed.), Frontiers in sociology of instruction (pp. 127–162). Springer.

Bryk, A., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for comeback. Russell Sage Foundation.

Cashman, 50., Sabates, R., & Alcott, B. (2021). Parental involvement in low-achieving children's learning: The office of household wealth in rural India. International Journal of Educational Research, 105(4), Commodity 101701.

Christenson, S. 50. (1995). Families and schools: What is the part of the schoolhouse psychologist? School Psychology Quarterly, x(2), 118.

Cohen, D. K., & Mehta, J.D. (2017). Why reform sometimes succeeds: Understanding the conditions that produce reforms that final. American Educational Research Journal, 54(4), 644-690. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217700078

Cooper, C. W. (2009). Parental involvement, African American mothers, and the politics of educational care. Equity & Excellence in Education, 42(iv), 379–394.

Crozier, 1000., & Davies, J. (2007). Hard to reach parents or difficult to attain schools? A discussion of home-school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents. British Educational Enquiry Journal, 33(3), 295–313. http://world wide web.jstor.org/stable/30032612

Dowd, A. J., Friedlander, E., Jonason, C., Leer, J., Sorensen, Fifty. Z. Guajardo, J., D'Sa, N., Pava, C., & Pisani, Fifty. (2017). Lifewide learning for early reading development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2017(155), 31–49.

Epstein, J. L. (1996). Perspectives and previews on research and policy for school, family, and community partnerships. In A. Booth & J. F. Dunn (Eds.), Family-school links: How practice they touch on educational outcomes (pp. 209–246). Routledge.

Epstein, J. L., & Sheldon, S. B. (2002). Present and deemed for: Improving student attendance through family unit and community involvement. The Periodical of Educational Research, 95(v), 308–318.

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, Grand. Yard., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. South., Clark Salinas, Grand., Rodriguez Jansorn, Due north., Van Voorhis, F. L., Martin, C. Southward., Thomas, B. One thousand., Greenfeld, M.D., Hutchins, D.J., & Williams, K.J. (2018). School, Family unit, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Corwin. https://us.corwin.com/en-us/nam/school-family unit-and-community-partnerships/book242535

Fan, X., & Chen, K. (2001). Parental interest and students' academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, thirteen(i), 1–22.

Ferlazzo, Fifty. (2011). Interest or appointment? Educational Leadership, 68(8), 10–14.

Gallego, F.A., & Hernando, A. (2009). School choice in Chile: Looking at the demand side (Working Paper No. 356). Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile.

Gersick, C. J. (1991). Revolutionary modify theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. The University of Management Review, 16(i), 10–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/258605

Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel. (2020). Price-effective approaches to ameliorate global learning: What does recent evidence tell use are "smart buys" for improving learning in depression- and middle-income countries? UK Strange, Commonwealth and Development Function, World Depository financial institution, and Building Bear witness in Didactics (BE2) Group.

Light-green, C., Warren, F., & García-Millán, C. (2021, September). Spotlight: Parental Teaching. HundrEd.

Henderson, A. T., & Mapp, K. L. (2002). A new moving ridge of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Annual Synthesis 2002. National Center for Family & Customs Connections with Schools, Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL).

Heracleous, L., & Barrett, M. (2001). Organizational change as discourse: Communicative deportment and deep structures in the context of information technology implementation. The Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 755–778. https://doi.org/ten.2307/3069414

Ho, S.C. (2006). Social disparity of family unit involvement in Hong Kong: Event of family resources and family network. The Schoolhouse Community Journal, 16(2), 7-26.

Ho, S.C., & Willms, J.D. (1996). Effects of parental involvement on eighth-form achievement. Folklore of Education, 69(ii), 126-141.

Hoover-Dempsey, K., & Sandler, H. (1995). Parental involvement in children. Teachers College Record, 97(ii), 310–331.

Hoover-Dempsey, K., & Sandler, H. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children's education? Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 3-42.

Horvat, E. Chiliad., Weininger, E.B., & Lareau, A. (2003). From social ties to social capital: Class differences in the relations betwixt schools and parent networks. American Educational Research Journal, forty(ii), 319–351.

Hughes, M., Wikeley, F., & Nash, T. (1994). Parents and their children'south schools. Wiley-Blackwell.

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Instruction, 42(1), 82–110.

Jukes, M. C. H., Gabrieli, P., Mgonda, N. L., Nsolezi, F. South., Jeremiah, G., Tibenda, J. L., & Bub, Chiliad. Fifty. (2018). "Respect is an Investment": Community perceptions of social and emotional competencies in early babyhood from Mtwara, Tanzania. Global Pedagogy Review, v(2), 160–188.

Kabay, South., Wolf, South., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). "And then that his mind will open": Parental perceptions of early babyhood education in urbanizing Ghana. International Journal of Educational Evolution, 57, 44–53.

Kao, G., & Rutherford, L.T. (2007). Does social capital nevertheless matter? Immigrant minority disadvantage in school-specific social uppercase and its effects on bookish achievement. Sociological Perspectives, 50(1), 27–52.

Kim, D. H., & Schneider, B. (2005). Social upper-case letter in action: Alignment of parental back up in adolescents' transition to postsecondary instruction. Social Forces, 84(2), 1181–1206.

Kim, S. (2018). Parental involvement in developing countries: A meta-synthesis of qualitative inquiry. International Periodical of Educational Development, 60, 149–156.

Kim, Y. (2009). Minority parental interest and schoolhouse barriers: Moving the focus away from deficiencies of parents. Educational Research Review, four(ii), 80–102.

Kraft, Thou. A., & Rogers, T. (2015). The underutilized potential of teacher-to-parent communication: Evidence from a field experiment. Economics of Instruction Review, 47, 49–63.

Lareau, A. (1987). Social course differences in family-school relationships: The importance of cultural capital. Folklore of Pedagogy, lx(2), 73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112583

Liedtka, J., Salzman, R., & Azer, D. (2017). Democratizing innovation in organizations: Teaching blueprint thinking to non-designers. FuturED, 28(3), 49–55.

Lohan, A., Ganguly, A., Kumar, C., & Farr, J.5. (2020). What's best for my kids? An empirical cess of primary school selection by parents in urban India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 14(1), 1-26.

Meadows, D. (1999). "Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a Organization." The Sustainability Institute.

Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. (D. Wright, Ed.). Earthscan.

Molina, A. V., Belden, M., Arribas, Grand. J., & Garza, F. (2020). G-12 teaching during COVID-19: Challenging times for Mexico, Colombia, and Peru. EY-Parthenon.

Munro, G. D., Ditto, P. H., Lockhart, Fifty. K., Fagerlin, A., Gready, One thousand., & Peterson, East. (2002). Biased assimilation of sociopolitical arguments: Evaluating the 1996 U.South. presidential contend. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 24(1), xv–26. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2401_2

Nishimura, 1000. (Ed.). (2020). Customs participation with schools in developing countries: Towards equitable and inclusive basic education for all. Routledge.

Paseka, A., & Byrne, D. (Eds.) (2020). Parental Involvement Beyond European Education Systems Critical Perspectives. Routledge.

Pradhan, M., Suryadarma, D., Beatty, A., Wong, M., Gaduh, A., Alisjahbana, A., & Artha, R. (2014). Improving educational quality through enhancing community participation: Results from a randomized field experiment in Indonesia. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(2), 105–126.

Reese, W. J. (2011). America's public schools: From the mutual school to "No Child Left Behind." The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Reeves, R. Five. (2017). Dream hoarders: How the American upper middle class is leaving everyone else in the grit, why that is a problem, and what to do most it. Brookings Institution Press.

Reimers, F. Chiliad., & Schleicher, A. (2020). Schooling disrupted, schooling rethought: How the Covid-xix pandemic is changing education. Organisation for Economic Co-performance and Development and Global Education Innovation Initiative, Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://globaled.gse.harvard.edu/files/geii/files/education_continuity_v3.pdf

Rudney, G. Fifty. (2005). Every Instructor'south Guide to Working with Parents. Corwin Printing.

Schaedel, B., Freund, A., Azaiza, F., Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., Boem, A. & Eshet, Y. (2015). School climate and teachers' perceptions of parental involvement in Jewish and Arab main schools in Israel. International Journal about Parents in Education, 9(ane), 77–92.

Smith, D. Yard. (2000). From Key Stage 2 to Cardinal Stage three: Smoothing the transfer for pupils with learning difficulties. Tamworth: NASEN.

Tschannen-Moran, Grand. (2014). Trust matters: Leadership for successful schools. John Wiley & Sons.

Turney, K., & Kao, G. (2009). Barriers to school involvement: Are immigrant parents disadvantaged? The Periodical of Educational Research, 102(iv), 257–271.

Un. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty Serial, 1577, 3.

Valdés, G. (1996). Con respeto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and schools: An ethnographic portrait. Teachers Higher Printing.

Vincent, C. (1996). Parent empowerment? Commonage action and inaction in instruction. Oxford Review of Teaching, 22(4), 465–482.

Weiss, H. B., Lopez, K. E., & Caspe, M. (2018). Joining together to create a bold vision for next generation family engagement: Engaging families to transform education. Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Widdowson, D.A., Dixon, R.S., Peterson, E.R., Rubie-Davis, C.G., & Irving, S.E. (2015). Why go to school? Student, parent and teacher beliefs about the purposes of schooling. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 35(4), 471-484.

Winthrop, R., Barton, A., & McGivney, E. (2018). Leapfrogging inequality: Remaking education to help immature people thrive. Brookings Institution Press.

Winthrop, R., & Ershadi, M. (2020, March 16). Know your parents: A global study of family beliefs, motivations, and sources of data on schooling. The Brookings Establishment. https://world wide web.brookings.edu/essay/know-your-parents/

Wolf, S., Aber, J. 50., Behrman, J. R., & Peele, M. (2019). Longitudinal causal impacts of preschool teacher training on Ghanaian children'southward school readiness: Evidence for persistence and fade‐out. Developmental Scientific discipline, 22(5), Commodity e12878.

World Health Organization. (2009). Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. World Health Arrangement.

Zuilkowski, Southward.South., Piper, B., Ong'ele, Southward., & Kiminza, O. (2018). Parents, quality, and school option: Why parents in Nairobi choose low-cost private schools over public schools in Republic of kenya'southward costless main education era. Oxford Review of Didactics, 44(2), 258-274.

Acknowledgments

This playbook was co-authored by Rebecca Winthrop, Adam Barton, Mahsa Ershadi, and Lauren Ziegler from the Center for Universal Teaching (CUE) at Brookings. Rebecca Winthrop is the master investigator, and the other co-authors are listed alphabetically given their equal contribution to the work.

The examples in the Strategy Finder were co-authored past Rebecca Winthrop, Adam Barton, Rachel Clayton, Steve Hahn, Maxwell Lieblich, Sophie Partington, and Lauren Ziegler.

This playbook was developed over a 2-year catamenia, with input from a number of collaborators, whose assist was invaluable.

First and foremost, CUE would like to admit the numerous inputs from the members of its Family Engagement in Educational activity Network (FEEN), a group of instruction decisionmakers representing public education jurisdictions, private school networks, and nonprofit, parent, and funder organizations from countries around the world. FEEN members accept shown their commitment to building ever stronger family unit-school partnerships, even during what have been the virtually challenging school years in recent retention. Members took time out of their schedules to attend regular virtual meetings, assist co-create the vision guiding the project (including selecting the proper name of the network), review and suit survey drafts, and connect the states to their communities so we could conduct surveys and focus groups with parents and teacher beyond their jurisdictions. They provided documentation of family engagement strategies inside their organizations, made time for follow-upwardly interviews with CUE, and provided thoughtful input into early drafts of the playbook. CUE is forever grateful for the commitment, comradery, and wisdom of the network members, whose contributions have helped ensure the playbook reflects the lived experiences from numerous contexts around the world. We are also deeply indebted to the thousands of parents and teachers who across each FEEN jurisdiction took the time away from their busy lives talk to the states and reply our surveys.

FEEN has grown since its inception and currently represents 49 organizations from 12 countries and one global private school chain with schools in 29 countries. The members are:

Aliquippa School District, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Allegheny Intermediate Unit of measurement, Pennsylvania, U.Southward.

Clan of Independent Schools of South Australia

Avonworth School District, Pennsylvania, U.Southward.

Brentwood Borough School District, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Buenos Aires Ministry of Education, Argentine republic

Butler School District, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Cajon Valley Union School District, California, U.S.

Chartiers Valley School District, Pennsylvania, U.Southward.

Doncaster Council, UK

Duquesne School Commune, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Fort Blood-red School District, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Ghana Education Service, Ghana

Hampton Township School District, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Himachal Pradesh Department of Instruction, India

Hopewell School Commune, Pennsylvania, U.Due south.

Inter-American Evolution Banking concern

Itau Social Foundation, Brazil

Keystone Oaks School Commune, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Khed Taluka Commune, Maharashtra, India

Leadership for Equity, Maharashtra, India

LeapEd Services, Malaysia

Learning Creates Australia

Lively Minds, Republic of ghana

Metropolitan Schoolhouse District of Wayne Township, Indiana, U.S.

Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, India

Ministry of Education, Colombia

Nashik District, Maharashtra, Bharat

Networks of Inquiry and Indigenous Teaching, Canada

New Brighton School District, Pennsylvania, U.Southward.

New Castle School District, Pennsylvania, U.Due south.

Nord Anglia Education

Northgate School District, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Parentkind, UK

Pune Municipal Corporation, Maharashtra, India

RedPaPaz, Colombia

Right to Play, Ghana

Samagra, Himachal Pradesh, India

School District 8 Kootenay Lake, British Columbia, Canada

School District 23 Key Okanagan, British Columbia, Canada

School District 37 Delta, British Columbia, Canada

School District 38 Richmond, British Columbia, Canada

School Commune 39 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

School District 48 Sea to Sky, British Columbia, Canada

Southward Fayette School District, Pennsylvania, U.South.

The Grable Foundation, U.S.

Transformative Educational Leadership Programme, Canada

Western Beaver School District, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Western Greatcoat Department of Didactics, S Africa

Young 1ove, Botswana

We are also securely grateful to our colleagues who reviewed our playbook offering incisive and of import feedback, suggestions, and critiques. Our last typhoon is measurably improved thanks to all of them taking time, often during weekends and holidays, to provide us with their feedback. Thank you to:

John Bangs, Madhukar Banuri, Alex Beard, Eyal Bergman, Jean-Marc Bernard, Sanaya Bharucha, Margaret Caspe, Yu-Ling Cheng, Jane Gaskell, Crystal Green, Judy Halbert, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Linda Kaser, Linda Krynski, Karen Mapp, Brad Olsen, Carolina Piñeros, Tom Ralston, Keri Rodrigues, Urvashi Sahni, Eszter Salamon, Michael Serban, and Heather Weiss.

In addition to the FEEN and peer reviewers, CUE conducted consultations and interviews with a number of stakeholders who provided thorough and thoughtful input over the years into the development of the inquiry, the playbook, and the examples featured in the Strategy Finder. We are particularly grateful to:

Akwasi Addae-Boahene, Yaw Osei Adutwum, Carla Aerts, Kike Agunbiade, Carolyne Albert-Garvey, Manos Antoninis, Anna Arsenault, Orazio Attanasio, Patrick Awuah Jr., Chandrika Bahadur, Rukmini Banerji, Peter Barendse, Alex Beard, Amanda Beatty, Gregg Behr, Luis Benveniste, Sanaya Bharucha, Elisa Bonilla Rius, Francisco Cabrera-Hernández, Paul Carter, Jane Chadsey, Mahnaz Charania, Su-Hui Chen, Yu-Ling Cheng, Elizabeth Chu, Samantha Cohen, Larry Corio, Richard Culatta, Laura Ann Currie, Tim Daly, Emma Davidson, Susan Doherty, Shani Dowell, Sarah Dryden-Peterson, Cindy Duenas, David Edwards, Annabelle Eliashiv, Joyce Fifty. Epstein, Jelmer Evers, Beverley Ferguson, Larry Fondation, Kwarteng Frimpong, Nicole Bakery Fulgham, Howard Gardner, Elizabeth Germana, Caireen Goddard, L. Michael Golden, Jim Gray, Crystal Green, Betheny Gross, Azeez Gupta, Kaya Henderson, Ed Hidalgo, Paul Hill, Michael B. Horn, Bibb Hubbard, Gowri Ishwaran, Maysa Jalbout, William Jeynes, Jonene Johnson, Riaz Kamlani, Utsav Kheria, Annie Kidder, Jim Knight, Wendy Kopp, Keith Krueger, Sonya Krutikova, Linda Krynski, Asep Kurniawan, Bobbi Kurshan, Robin Lake, Eric Lavin, Lasse Leponiemi, Keith Lewin, Sue Grant Lewis, Rose Luckin, Anthony Mackay, Namya Mahajan, Karen Mapp, Eileen McGivney, Hugh McLean, Bharat Mediratta, David Miyashiro, Alia An Nadhiva, Rakhi Nair, David Nitkin, Essie North, Hekia Parata, David Park, Shuvajit Payne, Chris Petrie, Marco Petruzzi, Vicki Phillips, Christopher Pommerening, Vikas Pota, Andy Puttock, Harry Quilter-Pinner, Bharath Ramaiah, Dominic Randolph, Niken Rarasati, Fernando Reimers, Shinta Revina, Karen Robertson, Richard Rowe, Jaime Saavedra, Suman Sachdeva, Siddhant Sachdeva, Urvashi Sahni, Eszter Salamon, Madalo Samati, Lucia Cristina Cortez de Barros Santos Santos, Dina Wintyas Saputri, Mimi Schaub, Andreas Schleicher, Jon Schnur, Marie Schwartz, Manju Shami, Nasrulla Shariff, Amit Kumar Sharma, Jim Shelton, Mark Sherringham, Manish Sisodia, Sandy Speicher, Michael Staton, Michael Stevenson, Samyukta Subramanian, Sudarno Sumarto, Vishal Sunil, Daniel Suryadarma, Fred Swaniker, Nicola Sykes, Eloise Tan, Sean Thibault, Jean Tower, Mike Town, Florischa Ayu Tresnatri, Jon Valant, Elyse Watkins, Heather Weiss, Karen Wespieser, Jeff Wetzler, Donna Williamson, Sharon Wolf, Michael Yogman, Kelly Young, and Gabriel Sánchez Zinny.

We are also grateful for the many individuals at CUE who helped make the playbook come to life in various ways, including: Eric Abalahin, Jeannine Ajello, Jessica Alongi, Nawal Atallah, Sara Coffey, Rachel Clayton, Porter Crumpton, Steve Hahn, Grace Harrington, Justine Hufford, Abigail Kaunda, Maxwell Lieblich, Shavanthi Mendis, Aki Nemoto, Sophie Partington, Katherine Portnoy, and Esther Rosen. In addition, nosotros would like to admit copy editing services from Mary Anderson, Jessica Federle, and Donna Polydoros and design services from Marian Licheri, Damian Licheri, Andreina Anzola, and Rogmy Armas.

The Brookings Establishment is a nonprofit system devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that enquiry, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of whatsoever Brookings publication are solely those of its author(south), and exercise not reverberate the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Brookings gratefully acknowledges the back up provided by the BHP Foundation, Grable Foundation, and the LEGO Foundation.

Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its commitment to quality, independence, and bear upon. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

The playbook is a living document that nosotros program to add to over time. If y'all have questions about the material or would like to see additional topics or information, please let us know at leapfrogging@brookings.edu.

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/essay/collaborating-to-transform-and-improve-education-systems-a-playbook-for-family-school-engagement/